- Home

- Sam Staggs

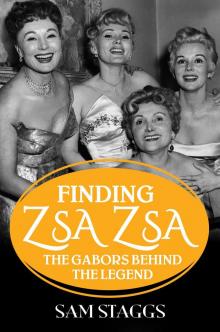

Finding Zsa Zsa

Finding Zsa Zsa Read online

FINDING ZSA ZSA

The Gabors

Behind the Legend

SAM STAGGS

KENSINGTON BOOKS

www.kensingtonbooks.com

All copyrighted material within is Attributor Protected.

Permission to quote the passage from the Yad Vashem website on pages 128-129 is courtesy of Yad Vashem.

Permission to quote the passage on page 134 is courtesy of The New York Post, NYP Holdings, Inc.

Kensington Books are published by:

Kensington Publishing Corp.

119 West 40th Street

New York, NY 10018

Copyright © 2019 by Sam Staggs

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any means without the prior written consent of the Publisher, excepting brief quotes used in reviews.

Kensington and the K logo Reg. U.S. Pat. & TM Off.

Library of Congress Card Catalogue Number: 2019932235

ISBN: 978-1-4967-1959-1

First Kensington Hardcover Edition: August 2019

ISBN-13: 978-1-4967-1961-4 (ebook)

ISBN-10: 1-4967-1961-1 (ebook)

For Tony Turtu

and

in memory of

Constance Francesca Gabor Hilton

Table of Contents

Title Page

Copyright Page

Dedication

Preface

Introduction: Five Nights in the Fifties

Chapter 1 - Gábor úr és Gáborné (Mr. and Mrs. Gabor)

Chapter 2 - The Mother of Them All

Chapter 3 - The Best Little Finishing School in Switzerland

Chapter 4 - Tempest on the Danube

Chapter 5 - Starter Marriages

Chapter 6 - Turkish Rondo

Chapter 7 - Eva and Eric

Chapter 8 - E.G., Phone Home

Chapter 9 - It Was a B-Picture Only to Those Too Lazy to Go Down the Alphabet

Chapter 10 - The California Gold Rush

Chapter 11 - Inferno

Chapter 12 - The Hour of Lead

Chapter 13 - West Hills Sanitarium

Chapter 14 - The World Was All Before Them

Chapter 15 - We Were Both in Love with George

Chapter 16 - Backstage at . . . We Were Both in Love with George

Chapter 17 - An Actress Prepares

Chapter 18 - Pink Danube

Chapter 19 - Husbands Get in the Way

Chapter 20 - Moulin Rouge

Chapter 21 - The Destroyer

Chapter 22 - Honky-tonk Gabor

Chapter 23 - It Didn’t Stay in Vegas

Chapter 24 - Mama, Don’t Cry at My Wedding

Chapter 25 - Ruszkik Haza! (Russians Go Home!)

Chapter 26 - If Mama Was Married

Chapter 27 - The Trujillo Stink

Chapter 28 - The Queen of Negative Space

Chapter 29 - Shatterproof

Chapter 30 - Dahling, I Love You, but Give Me Park Avenue

Chapter 31 - Another One Gone, and Another One Bites the Dust

Chapter 32 - Don’t Cry for Me, Philadelphia

Chapter 33 - The Ninth Circle

Chapter 34 - He Who Gets Slapped

Chapter 35 - Foul Deeds

Chapter 36 - Not Waving but Drowning

Chapter 37 - Could This Perhaps Be Death?

Chapter 38 - They Are All Gone into the World of Light

Acknowledgments

Selected Bibliography

A Note on Sources

Notes

Imagine a horoscope cast for us in our youth that failed to account for the shocking changes awaiting us in the future.

Marcel Proust,

Remembrance of Things Past

She generally gave herself very good advice, though she very seldom followed it.

Lewis Carroll,

Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland

Preface

As pop culture icons, the Gabors—Zsa Zsa, Eva, Magda, Jolie—were enormous fun. Watching them was like eating peanuts—you couldn’t stop. Even now, though departed, they remain household names. The Gabors are also taken seriously: in recent years, several female academics have written about them as proto-feminists. Indeed, under the frills they were strong, courageous women ahead of their time.

I set out to write a book that embraces this captivating aspect of these women even as it contradicts their frivolous, candy-floss reputation. In doing so, I wrote the book I wanted to read; surely every writer does the same. I hope that in these pages readers finally meet the Gabors nobody knew. Here, for the first time ever, they appear minus the artifice.

Clichés about this legendary family seem indestructible. I hope, however, to have punctured two of the silliest. The first is that they were famous for being famous. On the contrary, the Gabors were famous because they worked at it, and because they worked at their careers, every hour and every day for close to a century.

The other outlandish notion is that they somehow foreshadowed the Kardashians and others of that ilk. This one is nourished by those who know nothing of the Gabors and too much about the Ks, not one of whom has the sophistication, the poise, or the savoir faire of an Eva or a Zsa Zsa. The cosmopolitan Gabors, icons of elegance with color, style, flair, and wit, spoke multiple languages fluently, and their driving ambition landed them in hundreds of movies, TV shows, and stage productions. They ran businesses, raised money for charity, traveled the world, attracted countless friends in society high and low, and their bon mots became as famous as the wisecracks of Dorothy Parker and Mae West. Perhaps the Kardashians, along with Paris Hilton and other vapid celebrities, aspire to Gabor caliber and finesse. All of these no doubt enrolled in Gaborology 101. But they flunked the course.

Introduction: Five Nights in the Fifties

Why, one may ask, only five? After all, the blonde-hungry 1950s belonged to the Gabors as surely as to Marilyn Monroe, Jayne Mansfield, and to all those bottle-blonde starlets, models, and TV personalities. And also, of course, to countless imitators striving to live blonde lives in the postwar, conformist Eisenhower era, all of whom answered “Yes!” to Clairol’s advertisement: “Is it true blondes have more fun?”

Every night from 1950 to 1960 belonged to one Gabor or another. Zsa Zsa and Eva laid claim to most, but Magda—the redhead, the older sister—and Jolie, the irrepressible mother, grabbed the leftovers. Since these opening pages must limit the Gabor exploits of that teeming decade, I begin with an hors d’oeuvre: five pungent nights that helped entrench the Gabors in the spotlight. (Once on that magic media carpet, they scrambled and clawed to remain irresistible public dahlings.) After this appetizer, like Scheherazade I will unscroll the prodigious, hallucinatory, rollicking, and sometimes bitter lives of these four women, as well as the very different trajectories of Vilmos, father of the Gabor sisters, and Francesca Hilton, Zsa Zsa’s troubled daughter.

January 24, 1950

Opening night of The Happy Time at the Plymouth Theatre on Forty-fifth Street in New York. Written by Samuel Taylor, produced by Rodgers and Hammerstein, and set in Ottawa in the 1920s, it’s the story of Bibi, a French-Canadian schoolboy on the verge of puberty who learns something—but not much—about love. For 1950, however, in Cold War America, the play was looked on as a sex comedy, for Bibi stands accused by his schoolmaster of drawing dirty pictures, and much talk ensues among the grown-ups about nudity and the like. It turns out the boy didn’t do it—those doodles were the work of a guttersnipe classmate.

At home, the boy’s mother is a straitlaced Presbyterian while his more lenient father is a vaudeville musician and there’s an uncle who is—wink, wink—a traveling salesman. Then there’s Mignonette, the French maid, who gives Bibi

his first kiss and, as Life magazine demurely put it, “Bibi feels the first stirrings of manhood.” (This plot, of course, is Gigi transgendered.)

The French maid, however, speaks with a Hungarian accent, for she is played by Eva Gabor. Making her Broadway debut, Eva the minx outshone other cast members with her sparkle. Life again: “The play’s most decorative performer is Eva Gabor.” Others in the journeyman cast included character actors Kurt Kasznar, Leora Dana, Claude Dauphin, and Johnny Stewart as Bibi. Eva, too, felt the boy’s “stirrings,” for Stewart was sixteen years old and when he and Eva embraced, his manhood saluted.

Eva, who arrived in the United States in 1939 with the first of her five husbands, had appeared in half a dozen forgettable movies from 1941 to the end of the decade. Then, on October 3, 1949, she costarred with Burgess Meredith on CBS in the first episode of the network’s new series, The Silver Theater. This episode, broadcast live, was titled L’Amour the Merrier, and Eva played a French maid with a Hungarian accent. Richard Rodgers, sans Hammerstein, happened to watch television that night, and even in black and white Eva struck him as just the right article for The Happy Time. Had he guessed that she was thirty-one years old, he might have switched channels in search of a fresher soubrette.

The play ran for 614 performances, but Eva left the cast after a year and a half, in May 1951. Two weeks after the opening, Eva’s flawless face appeared on the cover of Life. That stunning portrait was the work of Philippe Halsman, one of the twentieth century’s best-known photographers. A few years later, a different photograph from the session, although equally strong, appeared on the cover of Eva’s autobiography, Orchids and Salami.

Eva’s Life cover flung open doors for her in New York that had remained shut in Hollywood. For a time, Eva’s face, her fashions, and most of all her accent popped up everywhere at once. A feeding frenzy swirled around this new exotic beauty whose past lay locked behind the Iron Curtain. But acting, more than allure, was her great passion. This she cultivated with love and labor, although glamour, and her accent, blocked the route. Like Marilyn Monroe, Eva studied with expert teachers and attended classes at the Actors Studio. Like Marilyn also, no one believed she wished to perfect the craft of acting.

July 23, 1951

Enter Zsa Zsa. With all eyes on Eva, Zsa Zsa was a distant dream that had not yet come true. Her resumé, had she produced one, would have shown that she possessed the requisites for a sort of louche fame, for in 1933, at age fifteen, she had been a contender in the Miss Hungary contest. Two years after that, she married an official in the Turkish government who often visited Budapest on political missions. With him, she lived in Ankara until 1941, when she embarked for the United States and arrived in New York on June 3rd of that year, along with twenty-one suitcases. In 1942 she married Conrad Hilton, the wealthy but tightfisted American hotelier whose anticipated generosity proved a sore disappointment to his spendthrift young wife.

Having deleted Conrad Hilton, in 1949 she married the actor George Sanders, who taunted and belittled her when she begged him to help her get a toehold in movies. Between Hilton and Sanders, Zsa Zsa cracked up and became the involuntary inmate of a psychiatric institution.

When Eva opened on Broadway in The Happy Time, Zsa Zsa had been Mrs. George Sanders for less than a year. Living in Hollywood yet segregated from the studios, Zsa Zsa felt betrayed by her nearest and dearest: George, the man she loved, and also the younger sister who made movies and who now posed for magazine covers and had New York at her feet, as the columnists liked to say. Zsa Zsa secretly accused Eva of a stroke of low cunning, for the Life cover bore the date February 6, 1950—Zsa Zsa’s thirty-third birthday!

While Zsa Zsa seethed with envy, news came one day of an offer to make a film—an offer for George, of course. They had now been married just over two years, and in the summer of 1951 George left for England to make Ivanhoe, in which he costarred with Robert Taylor, Joan Fontaine, and Elizabeth Taylor. Zsa Zsa begged and pleaded to go along. Her supplications echoed like forlorn yodels across the hills of Bel Air, where she lived with George and loved him with a full heart, though he was never under her spell and found her usually quite exasperating. In spite of his ill treatment, or as she later implied, because of it, she loved him until death.

“You stay home,” he told her. “You would just be bored and would make it impossible for me to work.”

In the empty house, she wept and phoned her mother in New York. But not until long-distance rates went down after five o’clock; the Gabors, even when prosperous, counted their spare change. “Oh, Nyuszi,” Zsa Zsa wailed, “I cannot live without him. I will kill myself.” (The girls sometimes called her “Mama,” though more often “Nyuszi,” or “Nyuszika,” pet names in Hungarian meaning “bunny rabbit.”)

Jolie had heard it all before. “Buy a new frock and charge it to George,” she counseled. “And throw in diamond earrings to match.”

When George learned of his mother-in-law’s advice, he called her “you fucking Hungarian!” But Jolie, having seen husbands enter and exit, knew that greatness lay in store for her Zsa Zsa, along with marital treasures far brighter than this disdainful man who spoke Russian to his brother when he wished to keep secrets from Zsa Zsa.

That brother, the actor Tom Conway, had grown up in St. Petersburg, along with George and their sister. Although Russian citizens, they were said to be descended from English stock and the Sanders family emigrated to England at the time of the Russian Revolution in 1917. (The family’s English heritage has subsequently been disputed. Late in her life, George’s sister came to believe the family to be pure Russian.)

Tom Conway worked steadily in pictures, although in character roles and smaller parts, unlike George, who had become a real movie star. Between films, Tom was a regular panelist on a new West Coast television show called Bachelor’s Haven. The show’s gimmick was advice to the lovelorn, always lighthearted and the sillier the better. (The heavy breathing of ABC’s The Bachelor and its spinoffs was unthinkable on fifties TV.)

On July 23, 1951, two days after George’s departure for England, Tom Conway phoned Zsa Zsa with an offer that she almost refused. “We’ve a vacancy on tonight’s panel,” he said. “Do be a love and help me out of a jam.” She balked. True, she was not easily intimidated, for she had traveled alone, during wartime, from Turkey across such risky terrain as Iran, Iraq, and Afganistan, finally boarding a ship in India for passage to the U.S. She had married three times and had woken up in a straitjacket in a mental ward. All that, yet she quailed at the thought of live TV. “No, dahling,” she said. “Your dear brother has told me a thousand times I have no talent.” Pause. “What would George say?” Two beats. “I’ll show that son of a bitch. What time are you picking me up?”

If the camera in that TV studio had been of the male gender, Zsa Zsa would surely have seen its manhood stirring, for it did everything but fondle her. And no wonder. Perfect skin, pure as vanilla ice cream, against her black Balenciaga gown. Diamond earrings and more diamonds around her neck and on her fingers. When she opened her red Cupid’s bow mouth, a feral accent spilled out that sounded like a snow leopard learning English.

During the show’s opening moments, the host commented on her jewelry. She shrugged. “Dahling, zese are just my vork-ing diamonds.” The audience roared; Zsa Zsa’s wisecracks kept them in stitches right up to the closing credits and calls inundated the switchboard. Soon fan letters flooded the station. A week later Daily Variety reported that Zsa Zsa was an “instant star” and had been invited as a regular on the show.

Bundy Solt, a childhood friend of the Gabor sisters, had come to Hollywood at the outbreak of World War II. Two days after Zsa Zsa’s dazzling debut, he phoned her and said, “Have you read the trade papers?”

She replied, “I do not know what means ‘trade papers.’ ”

“You dope,” he replied. “Hold the line.” And he read her the raves, which perplexed the brand-new celebrity. As far as she knew, she had done

nothing other than being Zsa Zsa Gabor.

When George Sanders returned from his long location shoot in England, he first thought it was Eva once more on the cover of Life. But no, it was Zsa Zsa, who adorned the issue of October 15, 1951. She had been too busy to inform him that she now had an agent, a manager, a dramatic coach, a PR team promoting her, and offers to appear in movies.

Back in New York, good-natured Eva felt kicked in the belly. She, who had toiled for years in drama classes, rehearsed scenes and monologues, showed up for cold readings, done screen tests and auditions—all that, and now her bossy, overbearing sister had become one of the greatest overnight successes in show-biz history. And all because of a raucous, unscripted appearance on TV.

January 9, 1953

In the press, Magda was often described as “the quiet Gabor.” And so she was, at least in public. In the family, she could raise her voice, flounce out of a room, spew invective, and slam doors as theatrically as the others. She had no theatrical ambitions, however, until one day a producer of plays for a regional theatre phoned to offer her a part in The Women, the acerbic comedy of manners written by Clare Boothe Luce. The play’s gimmick is that the female characters, in bitchy repartee, dissect husbands and boyfriends—and one another—yet no men appear on the scene. The 1939 film version, directed by George Cukor, starred Norma Shearer, Joan Crawford, Rosalind Russell, and Joan Fontaine.

When the producer told Magda why he was calling, she berated him. “You are an opportunist!” she hissed. “You want only a Gabor for publicity. I have never been in my life on a stage.”

Finding Zsa Zsa

Finding Zsa Zsa